Defending Our Modern Life ( Translated from original speech in Chinese )

Author: Ren ChongHao 任冲昊 (马平)

Source: https://www.guancha.cn/MaPing/2018_01_17_443440_1.shtml

We have just learned to eat

Since the release of "A Bite of China" in 2012, Luosifen (snail rice noodles) has become the signature dish of Liuzhou city, with Guangxi snail rice noodle shops now found throughout China. At the end of last year, National Geographic Magazine sent me to Liuzhou, Guangxi for reporting, where I specifically researched the history of Luosifen.

Regarding the origin of Luosifen, there are several local theories: some say it was invented in factory canteens as late-night meals for night shift workers; others claim it was created by food stand owners to quickly serve noodles to audiences leaving movie theaters; another theory suggests that when many travelers arrived by late-night trains needing food, shop owners only had snail soup and rice noodles left, so they improvised by combining them. The common thread in these stories is that Luosifen is definitely not an ancient food, nor was it created in home kitchens, but rather a fast food invented by modern food businesses for quick, mass production.

螺蛳粉 Luosifen

In fact, Luosifen naturally possesses the qualities of an excellent fast food.

First, it uses dried rice noodles rather than wet ones, making the ingredients easy to transport; second, the snails are pre-cooked into the broth, providing rich flavor and oils that can be quickly reheated; third, the toppings include dried tofu skin, pickled bamboo shoots, pickled vegetables, peanuts, and a small handful of greens—most of which have a long shelf life. These advantages are quite similar to instant noodles. Therefore, Luosifen's conquest of the national market has been achieved half through restaurant openings and half through packaged instant-style sales. Last year, the sales of packaged Luosifen from Liuzhou to the rest of China exceeded 3 billion yuan.

How long has the history of such a massive industry been? As mentioned above, the market demand of modern society came first, followed by the creation of Luosifen, so its history can't be very long. The three or four origin stories of Luosifen only trace back to the late 1970s at the earliest, making it not much older than I am.

Looking at signature foods from other cities, most actually don't have a long history either.

For example, Henan Hui Mian (braised noodles) first appeared in Zhengzhou in 1956, invented for mass production after restaurants underwent public-private partnership reforms.

河南烩面 Henan Hui Mian (braised noodles)

Wuhan Hot Dry Noodles (Re Gan Mian) were invented around 1930. A restaurant owner who prepared semi-finished noodles daily faced a dilemma: making too few meant not having enough, while making too many caused them to stick together. His solution was to mix the noodles with oil and sesame paste. This improvisation became extremely popular and evolved into the signature dish that represents Wuhan today.

武汉热干面 Wuhan Hot Dry Noodles (Re Gan Mian)

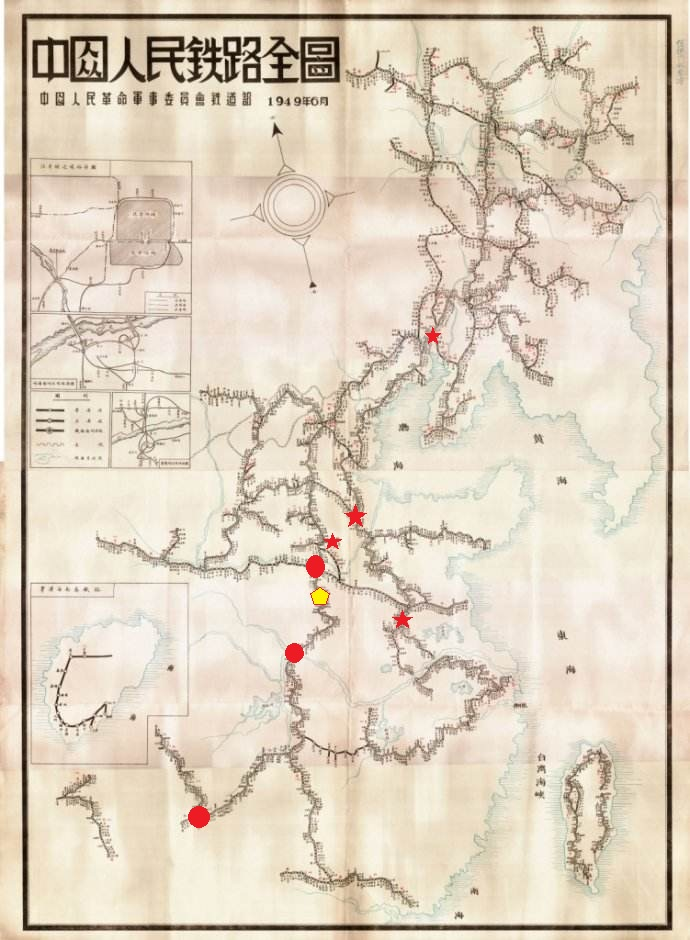

Luosifen, Hot Dry Noodles, and Henan Hui Mian share several common characteristics: simple preparation techniques, the ability to prepare large quantities of semi-finished products in advance, and quick assembly in response to market demand. Geographically, they share another commonality—they all originated in railway hubs. Wuhan, Liuzhou, and Zhengzhou are all locations with cross-provincial railway bureaus. In 20th century China, railways were the primary mode of transportation, bringing modern society and mobile populations. This is why railway hubs were the most likely birthplaces for foods that appeal to modern tastes. The fact that Henan Hui Mian originated in Zhengzhou—a railway hub that formed in the 20th century—rather than in historical capitals like Luoyang or Kaifeng, illustrates this point clearly.

Similar to these noodle dishes are China's four famous chicken dishes: Dezhou Braised Chicken, Henan Daokou Roast Chicken, Jinzhou Goubanzi Smoked Chicken, and Fuliqi Roast Chicken. Each corresponds to an important modern railway location. All use chicken—the most affordable meat—as their main ingredient. While their flavors differ, they all share low moisture content, portability, and long shelf life. Like Luosifen and Hot Dry Noodles, these foods are products of China's railway era.

中国人民铁路全图 1949 年 6 月 - Chinese railway map 1949 June

However, if we examine all the foods mentioned above, they share a common characteristic: a lack of fresh vegetables. Why didn't China's first generation of railway foods include fresh vegetables? Because vegetables and most fruits weren't suitable for railway transport. Railways could only follow fixed routes and couldn't efficiently collect vegetables produced in scattered locations. So while railway hubs had no shortage of mobile populations, grains, pickled vegetables, and seasonings, the supply of fresh vegetables wasn't necessarily abundant. For China's mobile population to enjoy delicious foods with a high proportion of vegetables at transportation hubs, they would have to wait until the highway era.

The representative food of the highway era is the Xinjiang Big Plate Chicken (Da Pan Ji) that appeared in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The correct name for this dish is Shawan Big Plate Chicken. Shawan County is situated between Urumqi on one end and Karamay on the other, connecting Xinjiang's largest city with its major oil field.

克拉玛依周边公路图 - Highway map around Kramay

Before 2010, Karamay had no railway, so the highway traffic density in Shawan County was much higher than the national average. This enabled the county to solve vegetable transportation issues quite early. As I mentioned earlier, chicken is the most economical meat, and when combined with green peppers, potatoes, onions, and chili peppers, it creates the familiar Xinjiang Big Plate Chicken. The spread of Big Plate Chicken along highways throughout China coincided with China's rise to become the world's largest automobile producer.

To summarize, a significant portion of the popular foods we see on the streets today emerged only in the last few decades. The first major reason is that before the advent of railways and steamships, there wasn't such a large mobile population to create demand, and consequently, there weren't many restaurants or food products catering to ordinary people. Before the Opium Wars, even easily transportable items like pickled vegetables were locally produced and consumed.

After the Second Opium War, British steamships entered the Yangtze River, and modern commerce and industry emerged in Wuhan and Shanghai. With the growing mobile population, a food market formed along the Yangtze River, which led to the creation of Zhacai (pickled mustard plant). It wasn't until 1898 that businesses in Fuling produced the first vat of Zhacai, but with the support of large markets in Shanghai and Wuhan, plus the later railway network, Fuling Zhacai had become a national fast food by 1940. Like Dezhou Braised Chicken and Hot Dry Noodles, it represents a typical food product from China's first industrial revolution.

Another factor contributing to the emergence of numerous delicacies in recent decades is the transportation of goods. I've already mentioned the example of Big Plate Chicken, and here's another: can you guess when Henan's Wang Shou Yi Thirteen Spices appeared? It was in 1959, two years after the Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge was completed. For thousands of years, due to transportation difficulties, spices were luxury items once they left their place of origin and entered different climate zones. When the Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge connected the Beijing-Guangzhou Railway, linking northern and southern China for the first time, northern people could afford spices. This led to the emergence of affordable mixed food spices in Zhumadian, a city on the Beijing-Guangzhou line. In 1959, these spices sold for just 0.1 yuan per package—another food product created by industrialized society.

The most crucial point, however, is that people in agricultural societies weren't in a position to be particular about food. People must first satisfy hunger before considering taste. Without sufficient grain, salt, and fats, all other delicacies become meaningless. When I started university in 1998, I had a roommate from an impoverished mountainous region who, before college, had always considered instant noodles a luxury food—simply because instant noodles quickly satisfied the need for grain, salt, and fat.

Let me give two more examples. My hometown is Pingquan in Hebei, famous for mushrooms—over 400,000 residents produce 500,000 tons of mushrooms annually. But when grain was scarce in the past, few people praised mushrooms as delicious because they're low in calories. Who has the appetite for such things before being full? Later, I visited Yingkou City in Liaoning, where they call mantis shrimp "xia pa zi." Locals told me that in the 1960s when grain was insufficient, only the poorest families would go to the seaside to gather mantis shrimp. Why did only the poor eat mantis shrimp? Because mantis shrimp have low calorie and fat content—the energy spent collecting them before being properly fed wasn't worth it. In that era, the best delicacy was simply a combination of grain, fat, and salt, with the typical example being rice mixed with lard. Does anyone still consider this a delicacy today?

Furthermore, China's coal production was very low then, and most rural families didn't have stoves—only a large hearth for both cooking and heating. So even with oil, stir-frying was a luxury. Even in my childhood during the 1980s, farmers around us would only prepare stir-fried dishes when important guests were visiting.

The truly traceable folk cuisines from hundreds of years ago are mainly stewed dishes, such as Northeast China's stewed pork with vermicelli.

One final note: there was no MSG in ancient times. The only sources of umami flavor were broths concentrated from old hens and seafood. Ordinary households and restaurants couldn't afford such expensive seasonings. Only high-end Lu cuisine, represented by Confucius Mansion dishes, would use sufficient chicken broth and seafood to create delicacies. Most people might have gone their entire lives without experiencing umami—the taste of monosodium glutamate.

Once Chinese people became wealthier, with grain, oil, and salt widely available, and ordinary households could use gas stoves and MSG, the Chinese concept of good food became completely different from that of agricultural times. The most typical example is Sichuan cuisine replacing Lu cuisine as the mainstream cuisine on Chinese streets. This is because Sichuan cuisine uses more fire cooking, less seafood, and fewer chicken broth-based dishes, making it better suited to the cooking techniques and dietary habits of the gas stove and MSG era. Its relatively stimulating flavors also cater to the demands of ordinary people.

In fact, similar to the previously mentioned Dezhou Braised Chicken and Wuhan Hot Dry Noodles, most Sichuan dishes have also appeared only within the last century. For example, Yu-Shiang Shredded Pork, Couple's Lung Slices, Sour and Spicy Noodles, Mala Hotpot, and Chongqing Noodles only emerged during the Republic of China period—making them younger than many people's grandfathers here today. Dishes like Mala Xiang Guo (Spicy Numbing Stir-fry Pot) and Wanzhou Grilled Fish appeared only in the 21st century—when I was nearly finished with university. Sichuan cuisine is equally a product of modern Chinese society.

Why have so many familiar Chinese foods emerged only in the last 100 years or even decades, despite China's agricultural civilization having thousands of years of history?

I can answer this question using elementary school arithmetic—3,000 years of history has several dozen times the advantage over the most recent 100 years; but the total population of modern society is dozens of times larger than that of most periods in ancient times, and the proportion of people able to enjoy fine cuisine is also dozens of times higher. When these two factors of "dozens of times" multiply, they naturally overwhelm the single factor of "dozens of times." Add to this the advancement of cooking tools, and the culinary culture accumulated by recent generations actually exceeds that of the previous several thousand years. Therefore, contemporary Chinese dietary habits are completely disconnected from agricultural society, and "A Bite of China" is, to a large extent, younger than even our parents.

The Weight of History

Let me expand on that arithmetic calculation to estimate our entire cultural heritage. First, I'd like to ask everyone to estimate how many people have lived on Chinese soil from the beginning of civilization to the 21st century.

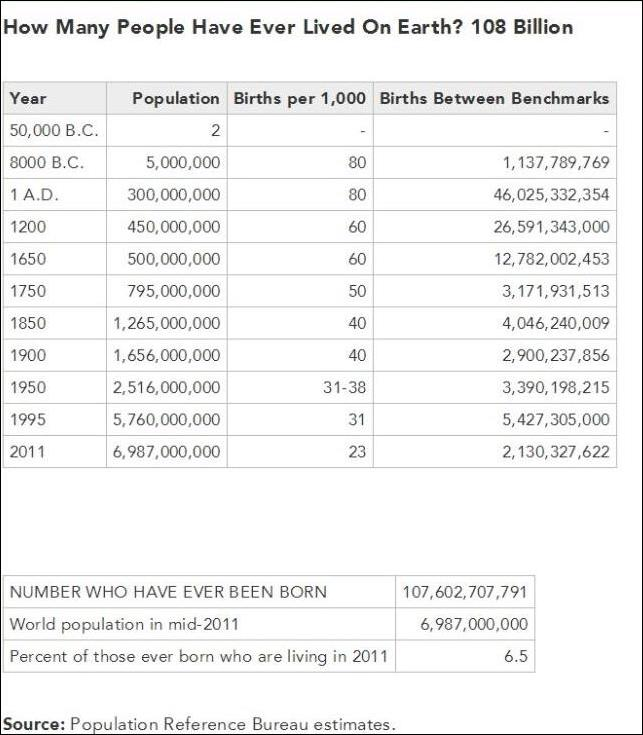

I don't know this figure precisely, but I've seen several global estimates suggesting that approximately 80-100 billion people have been born throughout human history. Regardless of dynasty or era, Chinese civilization has consistently accounted for roughly one-fourth to one-fifth of the global population. Therefore, the total number of Chinese people throughout history is approximately 20 billion. Conversely, if we calculate based on 5,000 years of civilization with 25 years per generation, that's 200 generations in total. Dividing 20 billion by 200 generations gives us 100 million people per generation, which is a conservative estimate at best. So the total of 20 billion is also a reasonable approximation.

How Many People Have Ever Lived On Earth? 108 Billion

These 20 billion people—how many have lived in New China? I have an estimate for this as well. The average life expectancy in China is over 70 years, and it's been 69 years since the founding of the People's Republic. Therefore, most people who were already born at the time of the country's founding have now passed away, while most of those born after the founding are still alive. The total number of Chinese people who have lived in New China is roughly the current population plus the population at the time of founding—approximately 2 billion. Compared to the 20 billion Chinese people throughout history, that's about a 1:10 ratio.

However, it's obvious that the proportion of cultural creation and inheritance cannot be calculated at a 1:10 ratio. To mention just one factor, among these 2 billion people of New China, the proportion who received education is certainly an order of magnitude higher than among the previous 18 billion. And the ability to create cultural products is generally proportional to education levels. So just on education alone, these 2 billion people could match the previous 18 billion. Not to mention that modern education is far superior to that of ancient times, and modern people consume and absorb knowledge through cultural products outside of school at least ten times more than people in ancient times. Roughly estimated, New China accounts for at least half of our total cultural heritage.

I anticipate some might question my comparison, asking how ancient education can be compared to modern education. How can elementary school students today be mentioned in the same breath as Li Bai and Du Fu? Indeed, many things cannot be quantitatively compared. But I can still offer some evidence.

I currently live in Suzhou Industrial Park, an area formerly called Weiting Town, which has been culturally advanced both within Suzhou and nationally. How advanced was it? During the Daoguang period of the Qing Dynasty, this single town had its own local chronicle, with a Hanlin scholar as chief editor—its economic and cultural level was at least equivalent to an ordinary county seat in inland areas. I happened to come across this local chronicle online and extracted some poems recorded in it, which should represent high-quality works by local scholars:

王鏊《唯亭》: 早朝时去晚朝回,陆市巴城迤逦来。咫尺唯亭看又过,人生行止信悠哉。

陈元素《送何仲先移家唯亭》: 周亲与我更芳邻,徙宅超然远市尘。路出东门船似马,湖当前岸浪如银。 谁能父子相师友,岂少贤豪互主宾。潮到此亭曾有谶,知君才不让前人。

李汾《唯亭》: 晓市争先集,唯亭水陆通。一江分上下,两庙划西东。 烟火千家爨,斜阳孤客篷。昔贤图八景,风雅有谁同。

查诜《武顺王祠》: 英姿飒爽镇三吴,日照唯亭庙貌孤。欲把美人配名将,中山祠在莫愁湖

Here are the poems mentioned:

Wang Ao's "Weiting": Early morning I depart, late evening I return, From Lushi and Bacheng, leisurely I come. A short distance to Weiting, glimpsed and passed again, Human life's comings and goings are truly unhurried.

Chen Yuansu's "Sending Off He Zhongxian As He Moves to Weiting": A fine neighbor becomes my fragrant companion, Moving his home, transcendent, far from market dust. The road out of the east gate, boats swift as horses, The lake at the front shore, waves gleaming like silver. Who else can have father and son as teacher and friend? How could there be a shortage of worthy hosts and guests? When the tide reaches this pavilion, there's an omen fulfilled, I know your talent will not yield to those who came before.

Li Fen's "Weiting": At dawn the market gathers, competing to be first, Weiting connects both water and land routes. One river divides upper and lower, Two temples mark west and east. Smoke and fire from a thousand homes cooking, Slanting sunlight on a lone traveler's boat. The sages of old depicted eight scenic views, Who now shares such refined elegance?

Zha Shi's "Temple of King Wu Shun": With gallant bearing he guards the Three Wu regions, Sunlight illuminates Weiting's solitary temple. Wishing to pair a beauty with a famous general, Zhongshan Temple stands by Lake Mochou.

I'm not sure how everyone views these poems. Setting aside the literary form, I feel that their literary talent, word choice, and themes are roughly at the level of middle school students—and not even the particularly good essay writers. I believe this represents the true face of ordinary intellectuals from ancient times. The reason we perceive ancient people as having high cultural levels is that only exceptional works have been passed down through history; everyday compositions simply didn't survive.

If we must make a comparison, I previously calculated a ratio: in the late Qing Dynasty, with a population of 300-400 million, about 20,000 xiucai (entry-level scholars) were produced annually. Today, with our population of 1.3-1.4 billion, four times that of the Qing Dynasty, we produce about 70,000-80,000 domestic and foreign-educated PhDs each year—also four times the Qing figure. In other words, proportional to population, today's PhD roughly corresponds to the ancient xiucai.

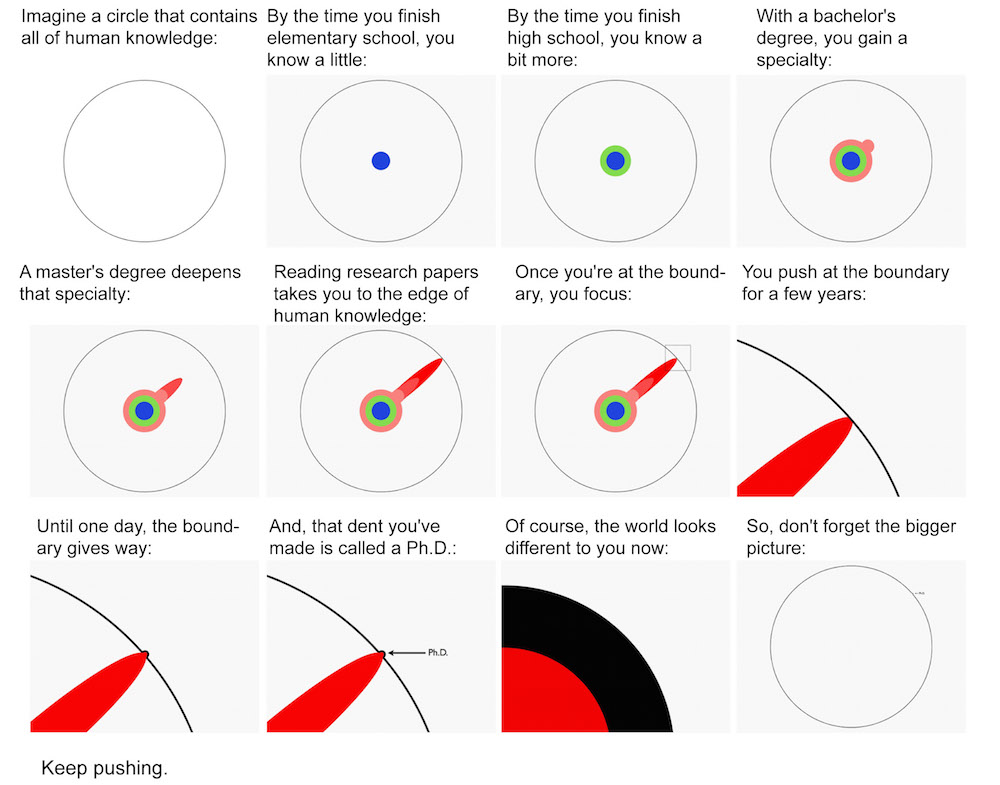

However, we know that xiucai represented the lowest tier of intellectuals in ancient times. 99% of them could at best be considered transmitters of culture rather than creators of new cultural achievements. Today, the situation is precisely the opposite: as a PhD, you must contribute previously non-existent knowledge to humanity through papers and experiments—in other words, every PhD is a creator of culture. There was a series of images analyzing the definition of a PhD, which I found quite fitting:

What does PhD mean?

This demonstrates that ancient society could only approach the cultural production efficiency of modern society if all intellectuals were creating culture. But what was the reality? Forget about one percent—even the most exceptional ancient intellectuals, perhaps one in a thousand, might not necessarily achieve anything that hadn't been done before. When I suggest that the cultural accumulation of the recent 2 billion people equals that of the previous 18 billion, I'm actually being generous to our ancestors.

Let me share some more data for perspective:

Our country has a tradition where unified dynasties not only wrote histories but also collected and categorized existing books, compiling them into "encyclopedias" for publication—essentially summaries of cultural achievements of their time. The most famous examples include the Ming Dynasty's Yongle Encyclopedia with nearly 400 million characters; the Qing Dynasty's Siku Quanshu (Complete Library of the Four Treasuries) with 800 million characters; and the Gujin Tushu Jicheng (Complete Collection of Illustrations and Writings from the Earliest to Current Times) with 160 million characters.

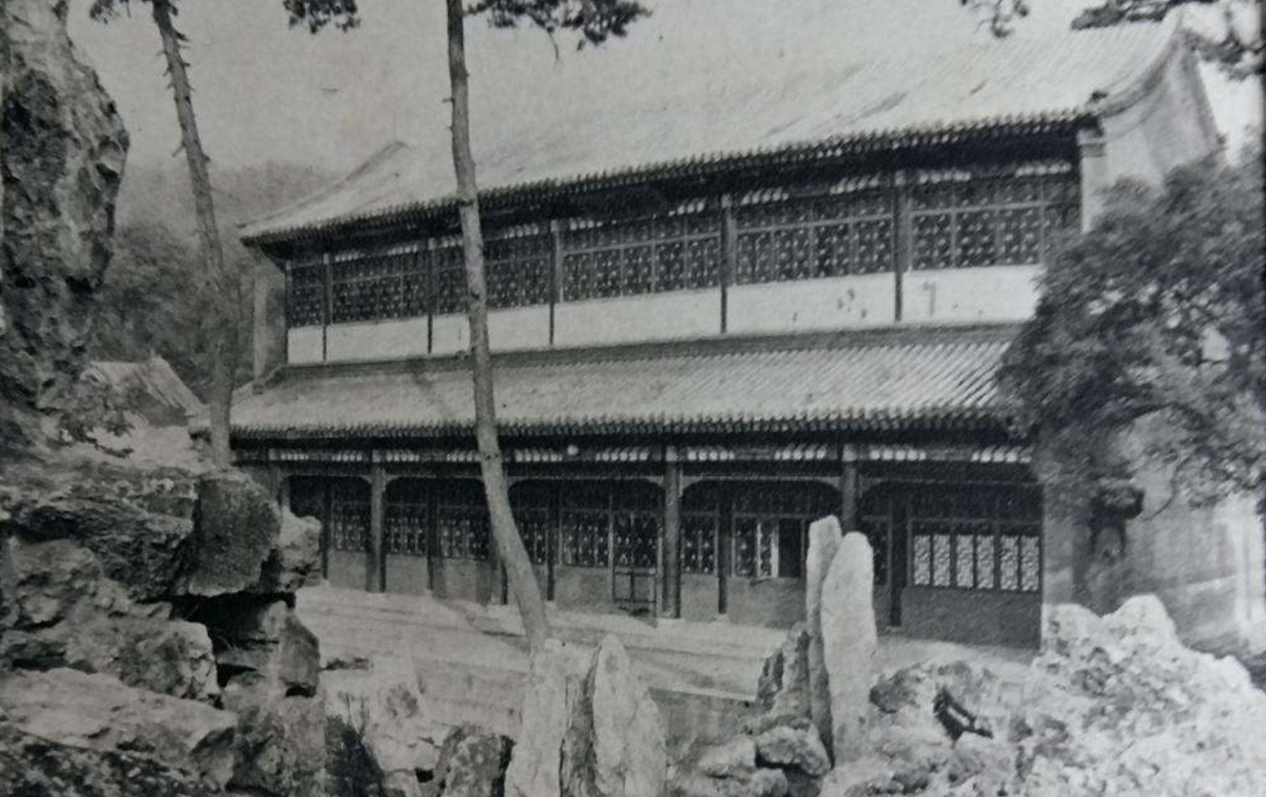

What does 100 million characters represent? At the end of last year, Zhihu sent me some statistics showing I had written 1.6 million characters on their platform and read 98 million characters, just shy of 100 million. Of course, most of my reading was quick skimming, but this suggests that without requiring intensive study, I could read through most pre-Qing cultural heritage in about a dozen years—certainly within a lifetime. This aligns with my direct impression of the Siku Quanshu—my hometown of Chengde has the Summer Resort with the Wenjin Pavilion, which houses a complete set of the Siku Quanshu. Let me show you a photo of this building to give you an intuitive sense of the quantity of ancient cultural accumulation:

文津阁 Wenjin Pavilion

Throughout the dynasties, we've accumulated only this much, which reveals an important point—ancient people's understanding of previous cultural heritage, such as Ming Dynasty people's understanding of the Tang Dynasty, was certainly inferior to ours. Today, any historical dynasty has hundreds of dedicated researchers nationwide. For example, the Song History Research Association alone has 30-40 directors and over 500 members nationally, discussing hundreds of papers at each annual conference. This far exceeds the number of people who compiled histories in ancient times. Besides the Song people themselves, the era that understands the Song Dynasty best is now, not any of the Yuan, Ming, or Qing dynasties.

Let me give you a tangible example. In ancient times, the greatest collectors were emperors, especially those who lived long lives and liked to showcase their cultural sophistication. Qing Emperor Qianlong collected countless paintings and calligraphy works, the best of which were moved to Taiwan. However, as these collections have been gradually examined in recent decades, researchers have discovered that more than half of his Song Dynasty art pieces were fake. Even the famous "Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains" scroll, preserved as an authentic piece in the imperial collection, is now largely considered inauthentic. This demonstrates that even in understanding history, ancient people were inferior to us today. Therefore, I believe that using 1900 as a dividing line, the cultural products accumulated after that date completely overwhelm the previous thousands of years in both quantity and quality.

"Who Am I?"

People are social animals, and society is constructed through cultural products such as morality and law. The cultural heritage of the entire society, as reflected in us as individuals, serves most importantly to define the concept of "who I am."

Imagine being asked to introduce yourself in an unfamiliar setting. How would you do it? Obviously not with your name and ID number, but by saying you're someone's child, an alumnus of a certain school, a player of a particular game—that's how you define yourself. And I, along with everyone here, share a common self-definition when facing the world—we are Chinese.

Yet this most universal definition is actually a very new concept. When my mother was young, working as a rural teacher in a mountainous area, one of the knowledge points she frequently taught was "I am Chinese." For thousands of years before that, most people not only didn't know this concept but didn't even consider "which country am I from" a meaningful question.

This question encompasses two cultural backgrounds that only exist in modern society. The first is a global perspective—knowing there are other countries parallel to China in the world; the second is national consciousness—recognizing oneself as part of the country, and that national policies have clear interactions with one's daily life. Ancient common people first didn't understand the global situation, and second didn't feel the country had any relationship to their lives. Changing emperors didn't change how they lived, unless sometimes they couldn't survive and actively sought to change emperors. Even decades later, life remained the same, so they almost never asked themselves which country they belonged to.

This way of life continued until the Opium War, when imperialism brought invasion to China. The traditional Confucian society and feudal warlords couldn't resist imperialism, creating our need to establish a modern nation. On the other hand, imperialism also brought advanced technology and ideas, giving us the feasibility to establish a modern state. The most intense invasion was Japan's in the 20th century, and the cultural concept of modern China began to form during this war. Even now, our national anthem's lyrics state "The Chinese nation faces its greatest danger," explaining why we initially needed to establish a modern country.

However, external threats only created a necessity—we had to unite, build a powerful military and developed industry to become a modern nation that imperialism would not dare invade again. But this necessity only describes the hardware of a modernized society without specifically explaining the cultural connotations of the term "Chinese." We still need to answer: Who are we culturally? Why do we consider each other compatriots? Is it because of some more ancient factors?

The definition of being Chinese certainly includes some ancient elements, such as Chinese characters. But many cultural symbols actually appeared quite recently, with histories similar to Sichuan cuisine.

For instance, the concept of "Descendants of Yan and Huang" was not synonymous with Chinese people before the 20th century. While Emperors Yan and Huang were important figures in the sequence of Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors, at most only some emperors and noble families claimed to have Yan and Huang bloodlines—ordinary Chinese people had no intention of acknowledging these ancestors. However, around 1900, everyone knew the Qing Dynasty was about to fall. Some revolutionaries used the identity of "Descendants of Huang" to inspire Han nationalism to overthrow the Qing; while other revolutionaries and reformists used the banner of "Descendants of Yan and Huang" to forge a Chinese nation, defining ethnic minorities as branches of Huang's descendants, intending not only to unify Han regions but also to inherit the legacies of the Qing and previous dynasties. This is how the concept of "Descendants of Yan and Huang" emerged. In 1912, the first year of the Republic of China, Sun Yat-sen sent people to worship at the Mausoleum of the Yellow Emperor, establishing the precedent for modern state worship of the Yellow Emperor.

When Sun Yat-sen and later the Kuomintang and Communist parties worshipped at the Yellow Emperor's tomb, it differed from previous dynasties' practices. Earlier worship treated him as an ancient emperor and deity, not particularly distinguished from other deities or ancient emperors. When the Republic of China conducted worship at the Yellow Emperor's tomb, they abandoned most traditional rituals from previous dynasties and specifically honored the Yellow Emperor, declaring him the ancestor of all Chinese people. This created the concept of "Descendants of Yan and Huang" in the 20th century. Later, during the early Anti-Japanese War period, the Kuomintang and Communist parties took turns conducting ceremonies—not out of genuine belief, but because both parties wanted to prove themselves as Sun Yat-sen's legitimate successors with the right to lead China against Japanese aggression. In 1944, as Japan launched its final major offensive, nearly forcing the Kuomintang to abandon Chongqing, the Nationalist government still found time amid the chaos to rename what was previously Zhongbu County to today's Huangling County, symbolizing its cultural authority as the modern state's central government.

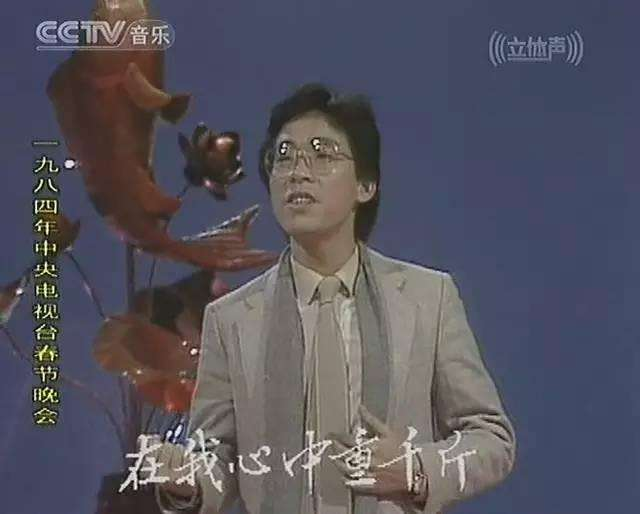

Besides the concept of "Descendants of Yan and Huang," we also refer to Chinese people as "Descendants of the Dragon (Loong)." However, in ancient times, the dragon(loong) was a water deity and royal symbol, never described as the ancestor of Chinese people. It wasn't until 1978, when the United States established diplomatic relations with mainland China, that the Kuomintang regime in Taipei felt abandoned by America and fell into confusion. Taiwanese singer Hou Dejian wanted to restate Chinese nationalism and wrote the song "Descendants of the Dragon(Loong)," creating this concept. In 1988, the Year of the Dragon(Loong), Hou was invited to perform this song at the Spring Festival Gala, which helped establish the concept in mainland China.

《龙的传人 MV》Descendants of the Dragon(Loong) MV

This demonstrates that choosing ancestors is a rather coincidental matter. If the revolutionary parties at the end of the Qing Dynasty had chosen Yu the Great or Fuxi as progenitors, we would have a different narrative today. Yet the cultural concept of Chinese people and the Chinese nation wouldn't fundamentally change because of this. This shows that our current definition of being Chinese doesn't rely on these cultural symbols invented in the 20th century.

So what does the concept of "Chinese" really mean? I can argue this from the opposite direction:

When we insult someone, we often use the phrase: "XXX, you're not human!" We all know that insults can't change another person's DNA—from a biological perspective, this statement is meaningless. So this phrase is actually spoken from a sociological perspective, suggesting that the other person doesn't observe the ethical and moral baseline, such as stealing someone's retirement savings, and thus has lost the qualification to be considered human.

Working backward from this phrase, we can see that the definition of being human comes from unified ethics and morality. The definition of being Chinese refers to your adherence to the mainstream ethics and morality of this country. We have a general consensus about what we approve of, what we oppose, what we joke about and ridicule. It's this shared understanding that allows us to recognize each other as Chinese.

However, morality itself is attached to lifestyle. When the Anti-Japanese War ended, our country had industrial and commercial cities, traditional agricultural regions, large numbers of pastoralists, and many ethnic groups on the verge of primitive society. The regional, class, and ethnic differences were far greater than differences between many countries. So I would say that at the end of the Anti-Japanese War, the concept of "Chinese" culturally had only taken an embryonic form and couldn't be said to have fully formed.

In the following decades, we first built nationally unified railway and highway networks, then worked to level income across the country as much as possible, and sent tens of millions of teachers to rural areas to establish schools. This finally popularized the concept of "Chinese" to a certain extent and forged a relatively unified set of values. By the 1970s, when my mother went to rural areas as a teacher, the cultural concept of "Chinese" was already close to being fully formed.

When was the concept of "Chinese" or "Chinese nation" finally established? I believe it was between the 1980s and the early 21st century. The most important cultural event in 1980s China was the popularization of television and rural power grids. Beginning with the 1983 Spring Festival Gala, we achieved for the first time a shared cultural experience that transcended region, urban-rural divides, and social classes, with most citizens watching the same performance. From then on, each year's Spring Festival Gala and popular TV dramas shaped a unified moral and ethical framework.

Reflecting on the most memorable programs from the Spring Festival Galas of the 1980s and 1990s, apart from a few special songs, the most impressive programs that created shared language among people of the same age were those life-oriented comedy skits and crosstalk performances. These skits were meant to guide values, establish images that the state wanted us to like, and satirize what the state wanted us to dislike. At the same time, these skits also had to cater to the thinking of most viewers, avoiding major social controversies. Life-oriented TV dramas like "Yearning" had similar effects to the Spring Festival Gala. Even most people's exposure to the Four Great Classical Novels began with TV adaptations that had been modified to suit modern tastes.

After more than a decade of guidance and exploration, we Chinese people formed a unified cultural ethic for the first time. We also came to believe that people from other regions would have similar ideas, so we wouldn't feel particularly out of place working in any corner of the country. By this point, the Chinese nation had truly established itself in a cultural sense.

《渴望》

In the 1990s, we entered the internet age of the 21st century. The internet era essentially "reviewed" the concept of Chinese culture formed in the 80s-90s. In the past, television could only transmit information one-way, but now the internet is bidirectional, capable of instantly spreading netizens' thoughts. Looking at recent internet hot topics, the main content revolves around social ethics and gossip news—for example, these past few days, the hottest news has been nationwide condemnation of two families blocking doors on high-speed trains, preventing others from passing. Each time similar internet news spreads, it shapes Chinese culture and strengthens the already-formed concept of the Chinese nation.

More importantly, the information age has significantly alleviated cultural differences between social classes.

The information age has two characteristics:

First, the unit production cost of cultural products is extremely high. In the past, a small theater troupe of dozens could provide end-to-end service from scriptwriting to performance. Now the cultural industry requires cooperation among thousands or hundreds of people and investments of hundreds of millions to create movies or variety shows that appeal to the entire nation. As for cultural industry hardware, such as mobile phones, laptops, and televisions, developing a competitive brand is even more expensive—billions in investment might not be enough to fund companies like Huawei or BOE for even a month.

Second, the distribution cost of cultural products is extremely low. Regardless of whether a film costs hundreds of millions or billions to produce, if I watch a pirated version, I only need an internet connection to download it. Even going to a movie theater or watching on a video website doesn't cost much. While phones and computers are somewhat expensive, even wage earners can afford them.

This creates an effect where no matter how wealthy someone is, they can't custom-create entirely separate cultural products and distribution platforms for themselves. For example, no matter how rich Bill Gates or Jack Ma may be, they're unlikely to produce films based solely on their personal tastes or develop specialized phones from scratch. Meanwhile, although wage earners are less affluent, they can still afford a smartphone or movie tickets. Last summer, I interviewed DiDi's Chairman Cheng Wei, worth billions, who, like us, plays Honor of Kings on weekends. This is unprecedented in any previous era. Despite significant class differences in our country, we haven't experienced the degree of cultural fragmentation that existed in ancient times.

Under these circumstances, the unified ethical views, moral perspectives, and customs formed in the pre-internet era have actually been strengthened to some extent in the internet age. Combined with nationwide popularized "hardware" like Luosifen, Hot Dry Noodles, and Sichuan cuisine in recent decades, we can finally roughly describe how a typical Chinese person lives and thinks. This is what I consider the true meaning of Chinese people and the Chinese nation.

When I say the concept of the Chinese nation or Chinese people was only finally formed at the end of the 20th century, it may sound sensational. But if we think carefully about it, consider when the characteristics that netizens attribute to Chinese people—such as being skilled in industry, adept at business, hardworking—were formed as self-identifications. In the mid-1980s, it wasn't like this. At that time, from intellectuals to ordinary people, there was unanimous criticism of the nation's small-farmer mentality, believing that we needed remedial lessons in industrial and commercial thinking. Going back several decades more, before the People's Communes developed agricultural water conservancy projects, both Chinese and foreign newspapers consistently criticized Chinese farmers for not knowing how to farm properly, saying they weren't as skilled in agriculture as the Japanese.

Therefore, the current substance of the Chinese nation is something formed in recent decades. Analyzing its formation process is very meaningful. In 2010, Huntington wrote "Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity." Our country is much younger and weaker than the United States, so we should more frequently ask ourselves: "Who is Chinese?" In Water Margin, Lu Zhishen had a line before his death: "As the tide comes in on the Qiantang River, today I finally know who I am." Today, I'll adapt it as my answer to this section: "As the modern tide surges forward, today we finally know who we are."

水浒传 TV - Water Margin TV

Human Perception

The next question is: since the concept of "Chinese" is largely shaped by modern society, why do most people believe it to be a tradition stretching back thousands of years?

First, it's due to our instinctive way of thinking as humans.

From biological and anthropological perspectives, we are primates who hunted on savannas and in forests, gathering fruits—a lifestyle that continued for hundreds of thousands of years. During this extensive period, humans' ability to transform the environment was weak; we could only adapt to nature's rhythms. Therefore, we subconsciously believe that our surroundings don't change, and that the rules passed down from our fathers and grandfathers are the most reasonable. Those who didn't respect existing rules would quickly be eliminated.

It was only in the last ten thousand years that we entered the agricultural age—between the first farmer and the 21st century, there are merely 300 to 400 generations. This time span is too short for fundamental changes in human genes; our brains haven't yet adapted to a changing world. Therefore, we're easily persuaded to believe that existing rules have been inherited for thousands or tens of thousands of years.

Secondly, there's the issue of our human perspective.

We tend to believe that what we saw in our childhood has always existed and represents unquestionable tradition. For example, my hometown was in a mountainous region where refined grains like rice and white flour were scarce—people could only buy them with ration coupons after finding work elsewhere. Before the 1990s, the staple food for farmers was corn. When I was young, farmers in my area would scold children who didn't study hard by saying: "If you don't get into vocational school, you'll eat corn flour your whole life!" At that time, I believed corn had been my hometown's staple food since ancient times, representing poverty and backwardness. It wasn't until my twenties that I accidentally heard my father mention that in the 1960s, the county sent technicians to teach farmers how to grow corn, and only then did our area's staple food change from sorghum to corn. I was shocked to realize that corn was also a new thing for my father's generation—a new food that tasted better and had more impact than sorghum.

Although the history of the Chinese nation is brief, it's still long compared to our lifetimes. For the post-90s generation of internet users, these are things they've seen since birth. So we sincerely believe that these Chinese cultural symbols and typical Chinese lifestyles have ancient heritage.

Therefore, when facing changes, our first instinct isn't to acknowledge development but to look to the past and find a historical model, framing change as a return to tradition. For instance, Western modern cultural development was termed the "Renaissance" by Westerners themselves; Wang Anshi's reforms claimed to revive the "Rites of Zhou"; and in modern times, Kang Youwei's reform proposals were written as "An Examination of Confucius as an Institutional Reformer." This habitual response manifests in our personal lives when we prefer to buy so-called royal products or ancient tribute items. Merchants cater to this desire by fabricating half-true, half-false legends connecting their products to ancient emperors or famous figures.

《孔子改制考》 "An Examination of Confucius as an Institutional Reformer"

From ancient to modern society, one of our greatest changes has been the increasingly close connection between ordinary people, the state, and society. In ancient times, imperial power rarely penetrated into villages. Farmers mainly interacted with local gentry landlords and clan members. Many farmers never visited their county seat in their lifetime or had dealings with official state employees. As for national policies, they were unheard of. Conversely, farmers felt no particular loyalty to the emperor or government.

But in modern society, beginning with the French Revolution, intensifying international military and commercial competition forced each country to establish increasingly powerful and complex governments that directly mobilize every individual to participate in competition. In turn, with the development of modern industrial and commercial society and rising education levels, individuals gradually recognized how government policies affected them and began making demands of the government, requiring it to be accountable to citizens.

This close connection between individuals and government is a new phenomenon for almost all countries. Yet during the Anti-Japanese War, we had to portray it as an excellent tradition of the Chinese nation, describing it as a cultural heritage passed down from Qu Yuan and Wen Tianxiang.

京剧 - Beijing Opera

During that specific anti-imperialist period, this type of cultural shaping was effective. However, when analyzing history as case studies, we cannot fully accept these cultural tools manufactured only in the 20th century. We must recognize which elements are actually products of modernization in order to learn useful lessons from history.

Further Reform

The Chief Architect(Deng XiaoPing) taught us that whether a cat is black or white, a good cat catches mice. Now that these 20th-century myths have played their historical role, why must I debunk them? Why can't we simply continue claiming that these 20th-century changes came from traditional culture?

We cannot.

Because modernization isn't a single shock wave, but a continuous process of change. If you describe cultural structures formed during the period of embracing modernization as traditional culture—as ancestral legacies that cannot be changed—you might get through current problems. But what about the next wave of reform?

Kang Youwei wrote "An Examination of Confucius as an Institutional Reformer" to advocate for Qing Dynasty reforms, originally positioning himself at the forefront of history. But Confucius obviously couldn't reform institutions twice. You can use this theory for reform only once. By the next historical turning point, ideas that once drove progress become social stumbling blocks. Historically, Kang Youwei indeed became entangled in his own ideology, becoming a steadfast royalist. In 1917, when Zhang Xun attempted to restore the monarchy, Kang was one of the planners. Later, when Feng Yuxiang expelled Puyi from the Forbidden City, Kang still frequently kowtowed to Puyi. We cannot be like Kang Youwei—inventing a tradition and then becoming constrained by it, left behind by the waves of modernization.

Furthermore, clarifying these early modernization cultural transitions isn't merely an ideological discussion—it involves breaking up interest groups. Any social structure, especially temporarily invented ones, gradually forms interest groups who are most eager to see the existing structure permanently maintained. If we don't clarify history, interest groups can easily seize control of public opinion in the name of defending tradition, ultimately causing social development to stagnate.

Take traditional Chinese medicine, which is a mixture of empiricism and mysticism. It does contain some effective prescriptions and treatments that can be valuable when modern medical resources are insufficient. But this promotion isn't about traditional culture—it's part of a modern welfare system, an attempt to transform traditional medicine using modern scientific principles. By failing to clarify this and instead promoting traditional medicine in the name of carrying forward traditional culture and maintaining national pride, we've created a temporary myth.

By the 21st century, modern medical resources have become abundant. What should be done now is to thoroughly reevaluate traditional Chinese medicine. Each prescription and theory should undergo strict monitoring just like modern drugs before use, and every traditional medicine practitioner should first study modern medical theory before exploring effective aspects of traditional medicine. However, on one hand, we created a myth of traditional culture when promoting Chinese medicine; on the other hand, the traditional medicine industry has formed a massive interest group with significant benefits in academic circles and the pharmaceutical industry. The combination of these factors has resulted in most traditional Chinese medicine moving increasingly further from the modern medical system. Herbal medicines can be marketed without rigorous drug reviews; practitioners can open practices without attending medical school, merely by memorizing ancient texts under a master. This not only harms people but also destroys the truly effective elements of traditional medicine. This blind worship of traditional medicine is a modern myth that should be abandoned.

Regulation of "Traditional Chinese medcine" operator exams

Beyond traditional medicine, there are many other movements resisting change in the name of tradition, yet behind them are not genuine traditions but temporary phenomena that emerged in the early stages of modernization.

Another example is how various liquor distilleries excavate elements of "alcohol culture" to add historical significance to their products and defend their high-proof liquors. In reality, the vast majority of people in ancient China rarely could afford to drink alcohol, and even when they did, it wasn't the high-proof white liquor we have today. Using tradition as justification to defend so-called alcohol culture is essentially protecting the interests of specific groups.

The issues mentioned above are at the societal level, but from a micro perspective, every family experiences conflicts between so-called tradition and modernity. Not surprisingly, most of these "traditions" are things formed only in recent generations. For instance, many families require children to memorize the "Standards for Students" (Di Zi Gui), claiming it's traditional culture. In fact, this text was created during the final period of Confucian society and only began to circulate after the Opium War—an extremely conservative work from the eve of traditional society's collapse, not at all a classic of traditional culture.

My family has a similar situation. I now eat more protein and fewer carbohydrates to lose weight. My mother opposes this approach, insisting that a variety of grains is most nourishing and best suited to Chinese digestive systems. However, eating grain to fullness every day is not actually a Chinese tradition—most people in agricultural society couldn't eat their fill. My mother's family only had enough grain to eat around the 1970s, so the "tradition" she uses to oppose my diet is merely a lifestyle from recent decades. If we don't actively dispel these modern myths and blindly respect so-called traditions, modern life becomes impossible to sustain. That's why today's title is "Defending Our Modern Life."

What do we do?

Having criticized pseudo-traditions at length, now I should present a defense plan. In summary, whether genuine traditions or false ones, there's no need for mystical halos. Most of our cultural heritage formed in the last one or two centuries. Just as we invented these cultures, we can certainly abandon them and create new ones. Even with genuine thousand-year-old traditional cultures, we must examine them carefully under modern social conditions to determine if they're still appropriate.

Specifically, I first recommend everyone learn some anthropology. When researching history and analyzing traditions, anthropology can give us courage.

Many say we should revere history, but even with reverence, human agricultural civilization spans only about ten thousand years—that's the extent of historical research. Before that was prehistory, when humans lived as biological entities. Anthropology observes humans from both biological and cultural perspectives, so its timeline includes not just the recent ten thousand years but the hundreds of thousands or even millions of years before. When my mother insists grains are most nourishing, I can counter from an anthropological perspective that even if this is a true tradition, it's only from the last ten thousand years—for millions of years before, we were omnivores, and specializing in certain plant seeds is actually against tradition.

From this perspective, anthropology's main function is to dispel the sense of sanctity around the phrase "since ancient times," because most sociological references to "since ancient times" are actually about the rules of agricultural societies. Anthropology not only covers a longer timeframe but also explores the interactions between human genetic biology and culture, uncovering patterns that may be more valuable than historical ones.

I previously read a story about Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia, where colonial officials summoned local natives and discovered that residents from more civilized agricultural regions were accustomed to bowing and kneeling, showing great deference to officials. Meanwhile, inhabitants from primitive jungle areas stood straight and didn't consider colonial officials superior. This case demonstrates that the concept of social hierarchy isn't an innate human tradition but rather a concept manufactured by thousands of years of class society—future societies may not necessarily have social hierarchies at all. When Marxism discusses communist society, it begins with primitive communism, not because Marx considered primitive communism admirable, but because he wanted to show us that class society is merely a product of a specific stage of human development, with no inherent legitimacy. With Marx's way of thinking, we can truly look at history and tradition objectively.

Marx's view of history is the historical materialism we learned in school. It's the tool we used earlier to analyze the Chinese nation and the concept of "Chinese." Through this analysis, we can see through the waves of history to the essence, recognizing that most cultural symbols constituting our lives are actually products of modern society. Acknowledging this isn't shameful—Americans have only 200+ years of history, yet they've led the world for the past century. Recognizing that our civilization is actually quite new doesn't prevent us from continuing to develop. In fact, people 100 years ago already saw this clearly. Liang Qichao's essay "Young China" should still be in middle school textbooks. Liang had already shed his historical baggage, and we in the 21st century shouldn't pick it up again.

Once we dispel our reverence for tradition and shed historical baggage, we can boldly invent new lifestyles to address newly emerging problems in our society. For instance, young people in big cities are reluctant to have children—they feel pressure after having one child and believe a second would impact their quality of life, causing birth rates to decline rapidly. Meanwhile, many who do have children lack the capacity to properly educate them, or even to avoid abuse. In recent years, there have been repeated news stories about children from Daliang Mountain becoming child laborers or performing in fighting exhibitions, only to leave again after being returned by the government, because their parents simply cannot provide normal schooling. In 2017, there were several news reports of parents abusing their children in public places, being reported to police by witnesses, but after police criticism and education, these irresponsible parents were allowed to take their children back home.

This series of events demonstrates that the nuclear family based on monogamy is increasingly unable to bear the full responsibility of raising children. China needs to quickly establish socialized childcare systems and revoke some parents' custody rights. Only this way can we ensure both the quantity and quality of the next generation, giving our society a future.

However, such actions would inevitably challenge the sanctity of the family, break with thousands of years of tradition, and redistribute guardianship rights away from direct relatives—certainly inviting criticism. But I believe that responsibility to the next generation is paramount. Currently, some children never have the chance to be born, while many others face problematic upbringings. Even if only considering our pension funds, we must design a new system. While family-based child-rearing may be a tradition of thousands of years, the nuclear family based on monogamy is itself a new phenomenon, widespread in China for only 30-40 years. Children needing over a decade of education to integrate into society is also a modern development. Facing these new challenges, there's no need to maintain failing old systems in the name of tradition.

Speaking of pension funds, all of China is currently worried about the aging population problem—concerned that a high proportion of elderly people will leave no one to support them. But from my perspective, is there really an aging problem? In the past, people in their forties and fifties already had damaged teeth, skin covered in spots, and difficulty walking. Now, seventy-year-olds are everywhere, dancing in squares, shopping for groceries, with glowing skin. This is clearly rejuvenation, so how has it become a social problem?

The issue lies in the retirement age. The past retirement age of sixty was based on the nutritional levels and medical conditions of that time—sixty-year-old workers had indeed lost most of their labor capacity. Today's sixty-year-olds are so healthy and often not doing physical labor, so they should definitely work a few more years. We've treated the sixty-year retirement age as too sacred and have been reluctant to change this tradition, which has created many social problems.

In conclusion, most of China's current problems should be analyzed through the lens of historical materialism and solved with new systems. We must boldly acknowledge that social conditions have changed and that traditional experiences cannot solve most of our problems. Only then can we maintain the rapid development of recent decades. In 2014, Southern Weekend published an excellent article—the most insightful cultural commentary I've seen in years—I recommend everyone read it:

南方周末:《文化解码》

According to traditional thinking, "establishing rites and creating music" was the work of sages; today's "sages" are "the people," and "new rites and music" need to gradually form through everyday interactions among everyone, never to be forced by the cleverness of just one or two individuals. Nevertheless, when a culture places all its hope in "returning to the past," it has already died.

Taking Initiative, Making Compromises

The Southern Weekend article used the phrase "establishing rites and creating music" to describe our creation of new systems. I really like this description because these four characters convey a sense of taking initiative. Rather than treating problems as they arise—treating the head when the head hurts, treating the foot when the foot hurts—it suggests proactively offering comprehensive solutions. This is how modern people should approach problems. Simply put, I hope everyone will consider how society should function rather than merely criticizing existing society. If everyone only says "no," the more anti-traditional we become, the more likely society will enter a state of stagnation.

For example, when a group goes out to eat, the worst scenario is when no one wants to order and everyone says "whatever"—the meal might never happen. Because "whatever" doesn't really mean anything goes; it means "you order, and I'll reserve the right to veto if I'm not satisfied." When everyone only fights for veto power, even those with ideas become unwilling to face everyone's criticism. In the end, everyone often has to wait until they're starving before eating.

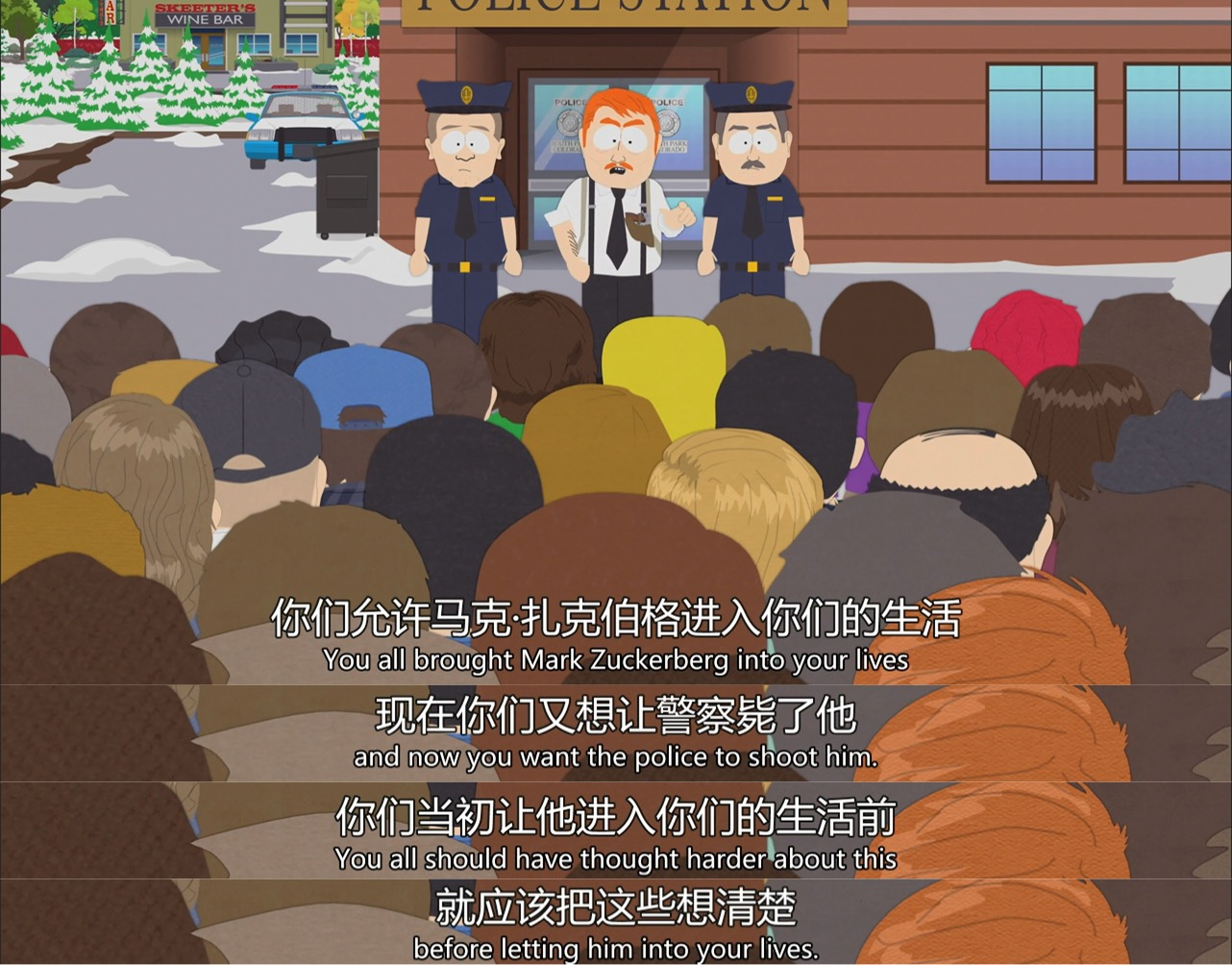

The United States is currently in this state where everyone says "whatever." The animated series "South Park," which debuted in 1997, has remained popular for 20 consecutive years.

South Park

Why is it so popular? Because most Americans can find jokes they appreciate in the show. While seemingly very anti-traditional, it pokes fun at everything in society. It mocks freedom of speech but also opposes speech control; it's against political correctness but also against political incorrectness; it ridicules others' beliefs while also mocking those who oppose religious freedom; it opposes illegal immigration while also opposing the expulsion of immigrants.

South Park represents America's current political situation, where people from every faction don't know what they actually want and raise their support by finding fault with others. The result? America elected Trump, one of the most ideologically conservative presidents, representing a major retreat on globalization issues. I see this as the turning point in America's decline.

Even in decline, America remains the world hegemon and many times more prosperous than us. China's society needs a higher development speed than America and requires far more social transformations. So while America can accept a conservative president, China must continuously pursue institutional innovation. Therefore, I hope we don't just say "no," but instead understand the operational costs of various social policies and offer constructive suggestions to society. We can't complain about urban management officers driving away street vendors one day, calling the government's law enforcement brutal, and then the next day, stuck in traffic, criticize the government for failing to manage even a single street properly.

As I just mentioned, when everyone only knows how to say "no," the result may be that the most conservative forces end up managing society, with established interest groups benefiting the most. Many ruling groups around the world have utilized this point to manage society long-term—seizing on one or two sensitive issues to provoke public anger, uniting people in the process of opposing certain things. Citizens oppose this and that, seemingly expressing many political demands, but in the end, these demands cancel each other out, and the same people remain in power—the same interest groups from decades ago. Taiwan province has already fallen into this trap, and the mainland must not fall into such a political pitfall. We must proactively create a new system to protect our path of modernization.

Regarding China's prospects, I'm relatively optimistic—at least compared to other countries, I have more confidence in China. Although my English isn't strong, working in media gives me opportunities to see political discussions among foreign netizens. I feel that in terms of humanities, social sciences, and political discussions, the average depth of Chinese netizens surpasses that of any major country. I suspect this relates to our decades of materialist education, to the "boring" political courses we all had to take, and to China's rapid development providing numerous sociological case studies from industrial society. Moving forward, I hope China can fully leverage this advantage and proactively build a system suitable for the productivity levels of the 21st century.

Industrial Confusion

I've done much rational analysis, so finally, let me share my understanding of the relationship between tradition and modernization from an emotional perspective. I know many people insist on tradition and oppose social change not just because of vested interests or firm belief in thousands of years of tradition, but because they've invested emotions in existing lifestyles. I say this because I myself am someone whose lifestyle changes very slowly.

I enjoy riding bicycles around, but because I learned to ride before geared bicycles were common, I still ride those straight-frame bikes from the 1980s without gears. I also prefer manual transmission when driving; whenever I drive an automatic, I keep reaching for the clutch and feel that an automatic doesn't feel like a real car. Even when riding trains, I miss the "ding-dong" sounds of the old rail joints, feeling that I sleep better with the noisier wheels. When I recall my life in the 1980s and 1990s, my most immediate impressions are of warmth, beauty, and stability.

However, if you asked whether I would want to return to life in the 1980s, I would firmly say no. My rational memory tells me that compared to 2018, not only were material conditions different, but information communication levels and personal development opportunities were worlds apart. Back then, the vast majority of people were confined to their narrow living spaces, exerting all their energy to secure the most basic modern living conditions. Even those with ability and ideas couldn't find places to showcase them. For those accustomed to the 21st century information age, the pre-internet era was essentially a large prison.

Though I clearly know the past wasn't actually wonderful, why do I still often feel nostalgic? I ask myself this question whenever my nostalgic emotions subside. One day, I finally understood. Compared to decades ago, modern society has made many material advances, but change happens too quickly—many opportunities pass before we can grasp them. In moments of disappointment, we long for something stable to comfort ourselves, like the familiar life of our childhood. We select the beautiful aspects to slowly reminisce, experiencing the beauty of traditional life. The most typical representation of this feeling is a poem by Mu Xin:

《从前慢》 木心 记得早先少年时 大家诚诚恳恳 说一句 是一句 清早上火车站 长街黑暗无行人 卖豆浆的小店冒着热气 从前的日色变得慢 车,马,邮件都慢 一生只够爱一个人 从前的锁也好看 钥匙精美有样子 你锁了 人家就懂了

"Slow in the Past" by Mu Xin

I remember in earlier youth Everyone was sincere and earnest A word said was a word meant Early morning at the train station Long streets dark with no pedestrians The small shop selling soy milk steaming with warmth In the past, daylight changed slowly Cars, horses, mail were all slow A lifetime was just enough to love one person The locks of the past were beautiful too Keys were exquisite and distinctive When you locked it, others understood

Modern people love to use this poem to praise tradition and the good old days. I admit, Mu Xin's writing is beautiful, but with a little scrutiny, we can find contradictions.

The poem mentions railways, mail, and a soy milk shop serving early train passengers. This appears to be a small town in the mid-20th century, corresponding to Mu Xin's youth. In his recollection, this is a stable society where small-town residents know each other, and peaceful life continues indefinitely.

However, we all know that small towns with train service and post offices—what kind of stability did they have in the 20th century? Before liberation, such towns inevitably experienced repeated wars, being occupied back and forth by the Japanese, the Northern Warlords, the Kuomintang army, and the Liberation Army. Even without war, I'm familiar with such towns—culturally completely subordinate to the nearest big city. Whatever becomes popular in the big city would be imitated here within months, and young people all want to leave. Every dozen years or so, the entire town's appearance would change completely, becoming unrecognizable. If someone tried to freeze a small town's life in a particular year, the first to protest would be the residents themselves, especially the young ones, because through railways and post offices they had discovered the outside world and absolutely wouldn't resign themselves to being left behind.

Even Mu Xin himself left to explore Shanghai in his twenties and went to America in the 1980s, only returning to settle in the small town in his later years. He could live there contentedly because he had experienced the wider world and could switch between two lifestyles at will, allowing him to appreciate the town's stable life. If he were to live his life again, I guarantee he would still go to Shanghai in his twenties and still go to America.

Therefore, while nostalgia feels beautiful, it's absolutely not a reason to abandon change. The more nostalgic we feel, the more we should seek our dreams in the future rather than being constrained by early industrialization lifestyles. Even if one day we grow old and, like Mu Xin, find a quiet place to settle down, we shouldn't stop young people from breaking through seemingly stable lives to design a new society.

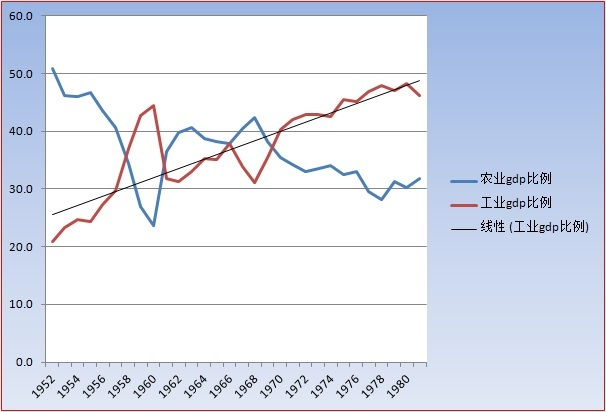

On this point, I think we should all learn from Chairman Mao's attitude. In 1966, Mao Zedong was already 73 years old—by all accounts, he could have, like Mu Xin, found a familiar place to spend his final years. However, he discovered that the great country he had established in the first half of his life was only a temporary project built on the foundation of agricultural society—a temporary project to drive away imperialism and quell warfare, not the true form of an industrialized society. In that same year of 1966, China's industrial GDP stably exceeded agricultural GDP for the first time, and the first generation of students educated in New China had progressed from elementary school through university graduation.

Blue: Agricultural GDP Proportion in China; Red: Industrial GDP Proportion in China

Industrial productivity determines production relations. When economic development is rapid, culture and institutions must also keep pace. Currently, our society's thinking is somewhat confused. Many people don't understand how current social culture formed and want to move backward in the name of tradition, refusing to allow social change to keep up with our productivity development, thus affecting the modernization process. That's why the theme of my speech today is defending modern life.

This defense of modern life contains two meanings. In the first half of my speech, I gave examples showing that most so-called "traditions" in society are actually new cultures invented during the modernization process. Many "traditions" people insist on maintaining are actually forms of modern life—we need to recognize the true face of the modernization process.

The second meaning is my hope that everyone can view history from beyond history, objectively evaluating our cultural heritage. Since traditions can be created at any time, they should also be discarded when necessary. With the development of productive forces, we will encounter countless new problems. We must create new cultural products for these new problems, allowing social institutional changes to keep pace with productivity development. Only then can we have future modern life. This modernized future is what contemporary Chinese people should value most and defend.